Pro-EU Win in Moldova’s 2025 Parliamentary Election, but Democracy Loses?

3 October 2025

Moldova is a key focus of attention for SEIM Analytics after numerous professional engagements. SEIM was serving as a long-term election observer for OSCE/ODIHR in Bălți, Moldova’s second biggest city, in the parliamentary elections in 2014 and again in the local elections in 2023, including as short-term observer in Rîșcani District in 2021 for the parliamentary election.

Disclaimer: In this article, SEIM Analytics comments independently on the 2025 parliamentary election with some links to the OSCE/ODIHR report, but without having been observing the election directly in the field. Consequently, this political commentary has no relation to the OSCE/ODIHR report available, here.

(Photo: The village of Iabloana outside the City of Bălți. Iabloana has a sizable Ukrainian minority, some 50%)

Moldovan citizens went to the polls on 28 September 2025 in what again was a highly-contested election. President Maia Sandu's Party of Action and Solidarity won 50,1% against the Patriotic Bloc that only achieved 24.2% and 26 mandates. It secures PAS 55 of the 101 mandates in the parliament, so an absolute majority, but mush less than in 2021, which equipped the Action and Solidarity Party (PAS) of President Maia Sandu with an absolute majority and conditions for a significant shift towards European integration. Other parties in the new parliament will be Chișinău-mayor Ion Ceban’s Alternativa (8% and 8 mandates), Our Party of Bălți-based Renata Usatii (6,2% and 6 mandates), and the pro-Romania-unification party PPDA of Vasile Costiuc that surprisingly passed the 5%-threshold (and secured 6 mandates with 5,4% of the votes).

The fear was that PAS would lose its majority, and be obliged to partner with pro‑Russian parties, even those that claim to be pro‑European but are tied to pro‑Russian or oligarchic interests (Ceban and Usatii), so the reform agenda of European integration would be compromised. Alternativa and Our Party could have played such kingmaker roles. The results hinder this. But as several significant parties were not allowed to stand for election, the question is if the elections were fair, one of several questions for this commentary.

Post-election, on 3 October, the CEC sanctioned PPDA for benefitting from a TikTok campaign (involving the far-right politician in Romania, George Simion) without declaring any expenses for online advertising. It was claimed PPDA has functioned as a "camouflaged electoral bloc" with the Alliance for the Union of Romanians party (which ran separately in the election). CEC left it to the Constitutional Court to decide whether to cancel the six mandates PPDA had won (with decision pending on 3 October). This issue has similarities to the disqualification of Calin Georgescu in the 2024 presidential elections in Romania.

Again, the diaspora had an important role in the election. It might have tipped the balance in the last elections in Moldova (especially in the EU referendum last year). This year, the pro-Russian bloc attacked Maia Sandu’s government for not doing enough for the diaspora, trying to win them. Even the right of the diaspora to vote was on the discussion table. The huge diaspora is predominantly pro-PAS, but the huge diaspora in Russia is voting for the opposition. Yet, by only opening two polling stations for the hundred of thousands of Moldovans in Russia, the result was clearly impacted in PAS-favour. CEC organized 301 polling station for the diaspora all together.

As in earlier elections, the electoral geography showed strong performance of the opposition (pro-Russian bloc and Our Party) in the North of Moldova including in second-biggest city of Bălți, strong results in Gagauzia in the South, while Sandu/PAS controls Central Moldova and southwest Moldova. Results again showed a divided Chișinău.

Disputed election financing: As with the 2023 local election, the presidential election in 2024 and the referendum, this election was overshadowed by Russian interference and the deregistration of key pro-Russian parties or candidates. Sandu's government and foreign observers and embassies have been claiming that Russia attempted to impact the vote through disinformation by social media bots and coordinated troll farms. It seems that millions of euros were available in Russian vote-buying schemes that included financial backing of pro-Russian parties. Also, influence through religious structures and more covert operations too place according to observers, all as part of Russia’s hybrid warfare.

PAS and Maia Sandu lost terrain in this election, as dissatisfaction in rising with costs of living. Inflation remains stubbornly high, GDP growth is slow the last two years (1%), and energy prices have been rising after cuts in energy access from Russia. One third is living under the poverty line, especially in rural areas. Still, the result brings relief for Moldova’s EU-partners and for Ukraine for whom Moldova’s geostrategic position makes it important for its defence against further Russian incursions in the Odesa and Black Sea region. Here, the separatist pro-Russian Transnistria Republic remains a point of security concern. To support Ukraine, Europe is therefore invested in the security of Moldova and the elections. For EU, to include Moldova in potential EU enlargement is a geostrategic answer to Russian invasion in Ukraine and the threats to Moldova. Yet, until recently, EU has not been sufficiently credible in that regard, as pro-Russian parties pinpoint in Moldova.

After its independence in 1991, EU has been slow to support Moldova, that has been suffering from a profound socio-economic crisis due to corruption and poor governance, with the result that more than a million of its population has left the small country, half a million to Russia, and the other half to the West. Only when the conflict in Ukraine developed in 2014, did the realization about the importance of Moldova increase EU and US attention to this poorest state in Europe. This helped the pro-EU Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS) of Maja Sandu win with a landslide in 2021. In March 2022, Chișinău applied for EU membership, and Moldovans reaffirmed this ambition and enshrined EU membership in its constitution in a very narrowly passed and disputed referendum vote in October 2024. Ahead of the 2025-election, there were symbolic but very important visit from the heads of state and government of the key European countries. EU provided assistance in combating cyberattacks, and massive investments were made so that Moldova's energy supply could be oriented towards the West. Meanwhile, Russia has always been invested, among other in the breakaway republic Transnistria. See a Deutsche Welle article and map of Transnistria here. Since 1993 the Transnistria conflict is being negotiated under the so-called 5+2-Format of the OSCE.

Also according to Deutsche Welle, the Russian ambassador, Oleg Oserov, recently pinpointed with reference to Ukraine that Moldova could be on a dangerous path if giving up its neutrality.

Photo (lower): Mihai Eminescu (1850–1889) was a Romanian Romantic poet, novelist, and journalist from Moldavia, generally regarded as the most famous and influential Romanian poet.

SEIM Analytics sees that after this election, Moldova will continue to remain divided and vulnerable. Russia continues to exert influence through media, financing, and the unresolved conflict in Transnistria, while EU must show resolve and give real prospects to Moldovans in order to enhance its leverage. If the war in Ukraine comes geographically closer, through another Russian crossing of the Dnieper River and insecurity in Odesa region, also Moldova will be impacted. Russian officials have recently revived rhetoric about claims to Odesa. For some Russian strategists, Tiraspol in Transnistria is the endgame, but there are numerous possible scenarios, stages, or solutions for this geographical area in the conflict about Ukraine. Establishing a transport corridor and port for Russia to the Transnistria Republic is one. In principle, all countries between EU and Ukraine should be able to choose multiple trade blocs and cooperation partners, including neutrality. Moldova is such a country that would profit from a balanced foreign policy and neutrality.

From an election technical perspective, the OSCE/ODIHR preliminary statement issued on 29 September points to some key issues that makes this election problematic. “A number of ODIHR Urgent Opinion recommendations on the initial draft law were addressed, but a few key issues remain unresolved.”

Regarding the work of the Central Election Commission (CEC), “occasionally politically aligned decisions on contentious issues called into question its impartiality and independence.” Regarding party registration, “CEC occasionally applied a formalistic and selective approach. Certain newly imposed candidate registration requirements were unduly burdensome and the pre-clearance of party eligibility by the Public Service Agency was not always clear. The decisions of the CEC and the Chişinău Court of Appeal in the last days before the election to revoke two parties’ eligibility, citing serious campaign and campaign finance violations, undermined the legal certainty of the electoral contestants’ status and given the timing limited their right to seek effective remedy, at odds with international standards.” (Art. 13 of the European Convention on Human Rights).

Moreover, “The new obligation for parties to maintain and submit a party membership register to the CEC and Public Service Agency (PSA) was upheld by a recent Constitutional Court ruling. However, failure to provide the required register can now result in the limitation of party activity, which the ODIHR Urgent Opinion states appears disproportionate and falls short of international standards” (p.6-7).

ODIHR pinpointed that “Partisan coverage in most media and limited investigative and analytical reporting, hindered voters’ ability to make an informed decision.” The PAS campaigning “may have blurred the line between party and State”. There were also other claims about misuse of public resources by the government.

ODIHR found that “targeted vote-buying schemes and disinformation campaigns, was credibly identified by the authorities and investigative journalists as originating from the Russian Federation. Proactive law enforcement efforts were seen to have a mitigating and deterring effect against vote buying.”

See the OSCE/ODIHR preliminary statement (p.11-16) for more details on the campaign, online campaign, and the campaign finance.

Yet, in political statements of support, OSCE-representatives on the OSCE/ODIHR press conference in Chişinău praised Moldova and its institutions for being resilient against hybrid threats and pressures.

Moldova has faced severe socio-economic problems since independence and massive emigration. EU has been slow to come to assistance. Such challenges have been instrumentalized on by pro-Russian parties.

The pattern of repeated deregistration of pro-Russian candidates:

For the 2025 election, on 3 August the Central Electoral Commission (CEC) removed four parties from the electoral race associated with the Victory bloc that was polling two-digit; Chance Party, Alternative Force for Salvation of Moldova, “Renaissance” (“Renaștere”), and Victory Party itself. Moldova already banned the Șor Party in 2023, affiliated with the oligarch Ilan Shor, but its networks tried to re-enter under these new labels. These removals were later confirmed by the courts.

On 26 September, two days before the election, also Heart of Moldova (PRIM) that was part of the Patriotic Bloc and the hardline pro-Russian and “unionist-with-Transnistria” Moldova Mare (Greater Moldova, PMM) were denied participation. PMM was rejected by CEC because its candidate list did not meet gender quota requirements, so for failing to adhere to administrative requirements. The PMM exclusion however could consolidate some votes toward the Patriotic Bloc and PSRM (Socialists), as these votes coming under the electoral threshold would have been lost anyway. (Thresholds of 5 and 7 percent of valid votes cast are in place for parties and electoral blocs, respectively. For independents, this threshold is 2 percent.)

Heart of Moldova (PRIM), officially registered on 2 December 2024 and led by the former governor of Gagauzia and 2024 presidential candidate Irina Vlah, was an important sub-structure inside the Patriotic Bloc, mobilizing especially in southern districts. PRIM was denied due to accusations of illegal financing of the party. Reasons for its exclusion on 28 September seem overly bureaucratic and non-proportionate.

The bans on the right to stand for election impacted the opposition bloc negatively in the 2025 election.

Also, the Liberal Democratic Party of Moldova (PLDM), the Agrarian Party, the Modern Democratic Party of Moldova (PDMM), ‘For People, Nature and Animals, and a few other parties were rejected for what seems like overly administrative reasoning.

The OSCE/ODIHR report finds, “In considering these decisions, the CEC occasionally applied a formalistic and selective approach and did not always communicate clearly and in advance about correctable shortcomings. (...) Furthermore, certain newly imposed candidate registration requirements proved unduly burdensome.” (p.10).

This key issue about disqualifications or blanket bans on political parties and candidates goes straight into the intersection of electoral integrity, international human rights standards, and domestic political competition in Moldova. Moldova’s Central Election Commission (CEC) has developed a notable practice of excluding political parties on technical or administrative grounds, such as for failing to update their registration at the Public Services Agency. More important though is the categorical exclusion of parties linked to the Victory Bloc. This follows earlier precedents observed by SEIM in Moldova, like the exclusion in 2014 of The Patria party (led by Renato Usatîi), again a few days before the parliamentary elections, officially on grounds of foreign financing (a case taken to the ECHR). Again, in 2021 and as observed by SEIM in Bălți City in 2023, after the Șor Party was dissolved by the Constitutional Court, subsequent successor organizations (e.g., “Chance Party”) were also barred. SEIM Analytics considers that the systemic use of exclusion makes it a political and legal instrument that puts both this and previous elections in Moldova in a problematic light.

Moldova is bound by international agreements and conventions, like:

· the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), Art. 11 (freedom of association) and Protocol 1, Art. 3 (right to free elections),

· the OSCE Copenhagen Document (1990), which commits states to respect the right to establish political parties freely and to stand for election without discrimination.

· International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), Art. 25 (participation in public affairs, elections).

From these standards, bans or disqualifications are permissible only under narrow and proportionate circumstances, such as preventing serious threats to democratic order, not on formal/administrative pretexts or because of political leanings. Administrative grounds (failure to update registers, gender quota miscalculations, irregularities in candidate nomination) can appear neutral, but when applied in ways that systematically affect certain opposition parties, they risk being seen as selective enforcement. Meanwhile, blanket exclusion of political opinions undermines pluralism.

The Venice Commission and OSCE/ODIHR have repeatedly warned that:

“restrictions on political parties are permissible only in exceptional cases, must be a last resort, and must be narrowly defined, pursue a legitimate aim (such as protecting democratic order or fundamental rights), and be proportionate and necessary to safeguard democracy” (OSCE Preliminary Statement 2025, p.6.)

Exclusions should be decided by independent courts, not primarily by administrative bodies.

The OSCE has consistently emphasized that excluding parties for their political orientation (rather than violent or unconstitutional activity) contradicts international obligations.

These exclusions therefore raise questions about the freedom of association and the right to stand for election. Moldova risks developing a narrowed political spectrum, where governing authorities or courts filter “undesirable” opponents under the guise of legal formalities. It has eroded public trust in Moldova but seemingly not international credibility, as it does not seem like EU cares much, as geostrategic issues are more important, so this step in Moldova’s EU accession process is ignored.

Supported by Western-financed NGOs and media, Moldovan authorities argue they are protecting the state from foreign interference and subversive actors (Russia) through the parties associated with the fugitive oligarch Ilan Shor. This is a legitimate concern, but one that must be pursued with proportionate, legally predictable tools. Moldova follows here in the steps of Ukraine, which also have restricted “pro-Russian” parties after 2014, citing security. Yet, some of the justification for excluding pro-Russian or other parties seem political; other are based upon unnecessary administrative failures. The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace has argued that the "pro-Russian" label had been “increasingly instrumentalized” against the opposition. (Consolidating Power, Losing Ground: Moldova Risks Repeating Past Mistakes Ahead of Fall Elections | Carnegie Endowment for International Peace)

SEIM Analytics regards that Moldova’s difficult balancing of sovereignty and security concerns risks undermining political pluralism and democracy. Voters must be allowed also to make unpopular or controversial choices, unless there is clear and imminent danger (e.g., incitement to violence). Although, Moldova has chosen the path to EU, if circumstances change, in theory also other trade blocks offering better conditions or possibilities can be relevant for cooperation. EU has neglected Moldova for decades, until Moldova now is needed for geopolitical reasons. There can be no law forbidding Moldova to change direction, and voters must be allowed to vote accordingly.

Blocking parties in defense of democracy and Moldova’s sovereignty and EU path is problematic, even if against potential Kremlin influence and due to alleged cited national security risks. It can be labelled political repression. It might deepen the domestic polarization, and continue to lower the turn-out as voters are not given a real choice. The deregistrations narrow the playing field for pro-Russian forces and also risks legitimacy debates about whether the election is fully fair. One solution is to have a more robust registration process, so that parties are excluded in an earlier stage and not shortly before the election. To facilitate this, the state institutions must be strengthened. This is also necessary to tackle illicit campaign financing and to increase the transparency of party financing.

Also, on the pro-EU side there are worrying signs. The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace finds in a report Western-funded civil society to “have become an extension of governmental capacity.” An “ecosystem of Western-funded civil society and European institutional channels” has been built up to benefit PAS. Yet, “this approach risks further hollowing out Moldova’s already fragile mechanisms of civic oversight and pluralist politics.” Also, a degree of “symbiosis" between some media outlets and the government has developed.

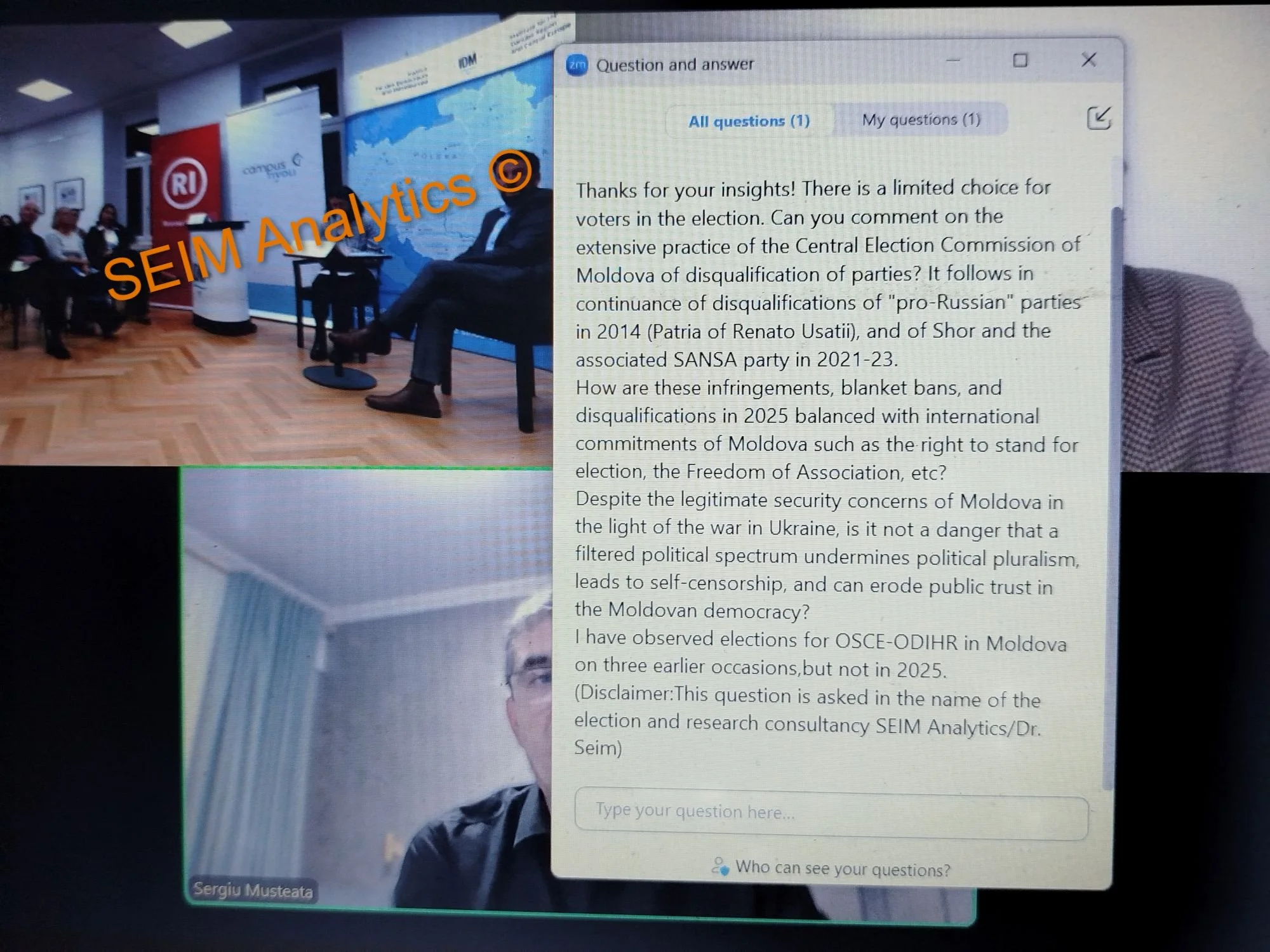

SEIM Analytics formulated a wider question on this issue on the public event “Parliamentary Elections in Moldova 2025” on 24 September of Institute of Danube and Middle-Europe (IDM) and the Renner Institute in Vienna with IDM director Sebastian Schäffer and the two Moldovan historians Svetlana Suveica and Sergiu Musteață: See this IDM event here!

Participating at this public session, in the name of SEIM Analytics the following question was asked to the panelists: “Thanks for your insights! There is a limited choice for voters in the election. Can you comment on the extensive practice of the Central Election Commission of Moldova of disqualification of parties? It follows in continuance of disqualifications of "pro-Russian" parties in 2014 (Patria of Renato Usatii), and of Shor and the associated SANSA party in 2021-23. How are these infringements, blanket bans, and disqualifications in 2025 balanced with international commitments of Moldova such as the right to stand for election, the Freedom of Association, etc? Despite the legitimate security concerns of Moldova in the light of the war in Ukraine, is it not a danger that a filtered political spectrum undermines political pluralism, leads to self-censorship, and can erode public trust in the Moldovan democracy? (Disclaimer: This question is asked in the name of the election and research consultancy SEIM Analytics / Dr. Seim) “

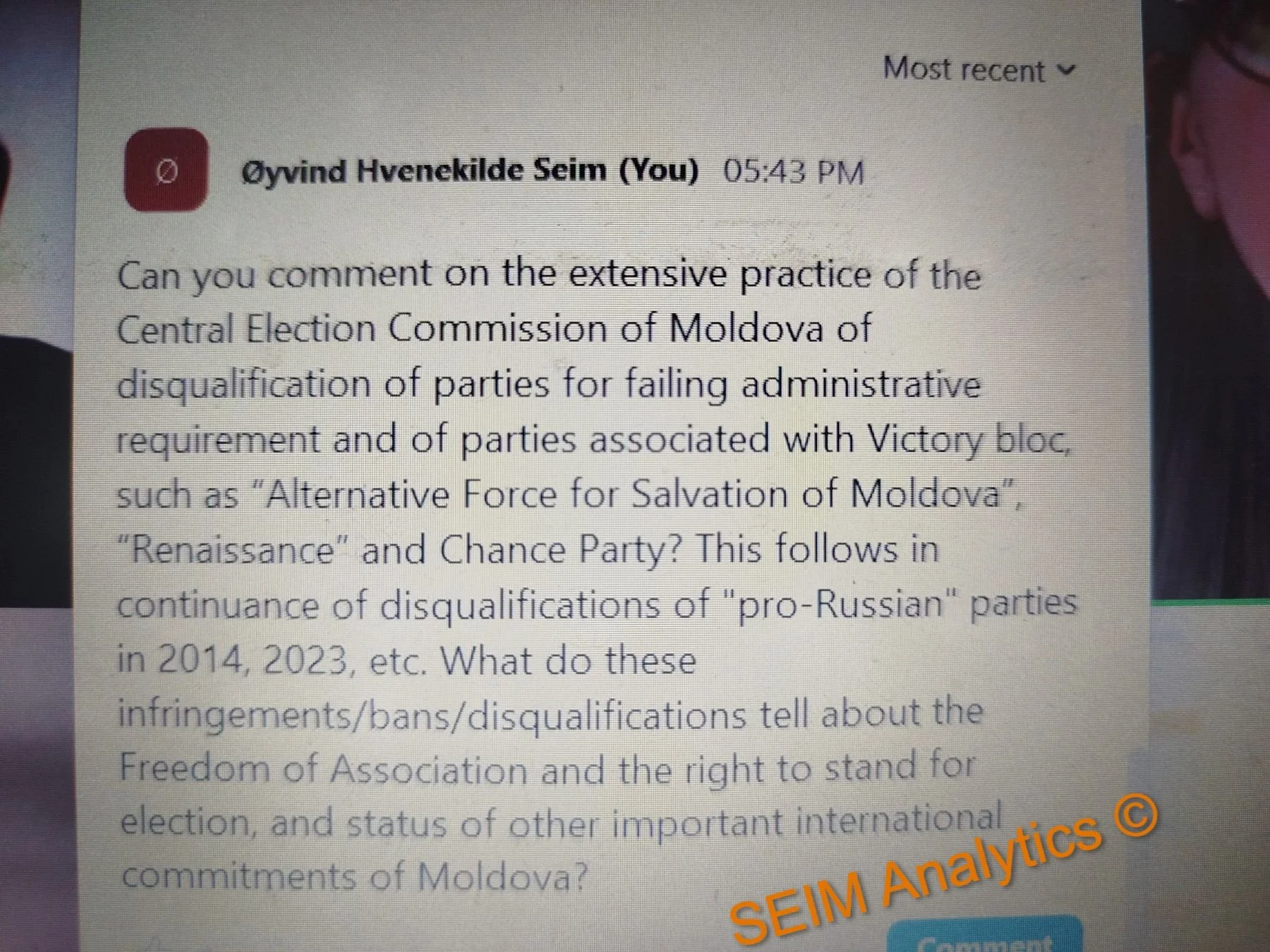

This problematicity SEIM Analytics also voiced shortly on the online meeting What's at stake in Moldova's 2025 Parliamentary Elections? 23 September 2025 of the German Southeast-Europe Association (Südosteuropa-Gesellschaft) on 23 September moderated by the Vienna-based FAZ journalist Michael Martens.

At this Youtube accessible discussion meeting, also the link to Romania and Calin Georgescu was made, and it was claimed that at least 65 people in his network also campaigned for the opposition in Moldova. Yet, in comparison, voters from Moldova were strongly supporting the liberal election winner Nicusor Dan on 18 May 2025, so cross-border election impacts are multifaceted. The last decade, some 430.000 Moldovan shave received Romanian citizenship. According to Romanian government figures, about 858,000 Moldovans have acquired Romanian citizenship since 1991.

See a SEIM Analytics report from the 2025 presidential election in Romania.

More background on Ilan Shor? See an informative article (in German) in the Austrian ORF on the social policies of Ilan Shor in Orhei and beyond: Draht in den Kreml: Moldawien wird Oligarchen nicht los - news.ORF.at

Earlier visits of SEIM to Moldova have gone to Tiraspol in Transnistria, Comrat in the Autonomous Territorial Unit of Gagauzia, to Cahul, Cricova Winery, and the capital Chișinău. Photo material is available. Go to Photo Sale - Moldova!