The Babiš Election Victory in Czechia, and the Contrasts to Other Right-Wing and Populist Movements in Central Europe

6 October, 2025

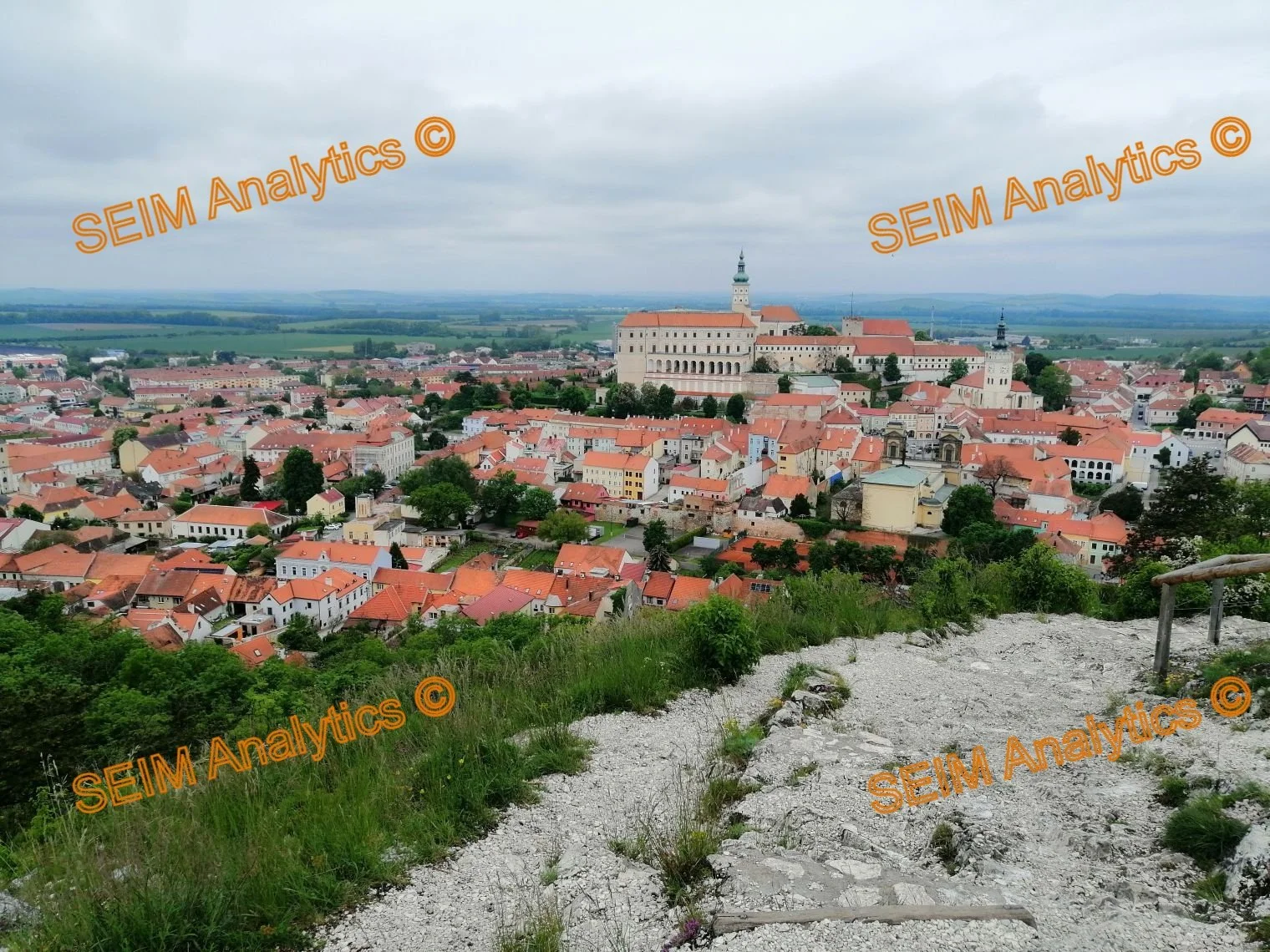

Photo: from Brno, Czechia’s second biggest city

SEIM Analytics has targeted emphasis on elections in Southeast, Eastern, and Central Europe (its post-communist countries).

This political commentary describes the Babiš project and reasons for his election win in Czechia in some more detail and also positions it towards other populist EU-sceptical projects in Central Europe, like those of Orban and Fico in Hungary and Slovakia.

SEIM has also earlier published about elections in Czechia, for instance in the Norwegian daily Klassekampen 23 November 2000 (De konservative seiret i Tsjekkia).

Read more about SEIM Analytics long-term explorative, analytic, and academic engagements with Czechia on thematic Czechia and East Central Europe page and on Czechia Photo Sale page.

Parliamentary elections were held in the Czech Republic

Elections were held on 3 and 4 October 2025 for the 200 members of the lower house of the Parliament. The result was a clear victory for the former prime minister (2017-21) Andrej Babiš and the ANO party over the Spolu (Together) coalition. Spolu consisting of the centre-right Civic Democrats, TOP 09, KDU-ČSL, was in power since 2021 supported by the “Pirates and Mayors” (PirSTAN: Pirate Party + Mayors and Independents). ANO means “Yes” but is also an acronym for “Action of Dissatisfied Citizens.” It achieved 35% of votes and 80 mandates, 8 more than in 2021.

While Prague was won by Spolu, where also Pirates did well, ANO’s best results were in the industrial regions like Usti nad Labem in the North and Morava/Silesia in the East, but also post-industrial regions like Karlovy Vary (especially in Sokolov and Cheb that have suffered socio-economically after the collapse of its mining and heavy industries in the 1990s). The South Moravia region with the city of Brno and Central Bohemia around Prague saw less convincing ANO wins over Spolu than elsewhere. Thus, ANO can be seen as less strong in the larger urban centers. Voters voting abroad were overwhelmingly and strongly against ANO.

ANO is now set for coalition negotiations with right-wing SDP (7,8% and 15 mandates) and the populist Motorists Party (with 6,8% and 13 mandates). Yet, with the Pirate & Green coalition achieving 9% and 18 mandates, the government-Pirate alliance performed better than polling suggested, winning 92 seats. Both, Pirates and Spolu will send many women politicians to the new parliament. The leftist Stačilo! - also a potential Babiš partner - did not cross the electoral threshold of 5%. Indeed, Babiš was fearful of "lost votes," that would go to parties finishing below the electoral threshold. In 2021, there was over a million such lost votes, over a fifth of the total votes cast. The good ANO-campaign and radical rhetoric might even have taken over many SDP and Stačilo! votes. On the other hand, now Babiš and ANO can manage without Stačilo! However, cooperation with the SPD (Freedom and Direct Democracy), might create problems for Babiš, as SPD embodies many fringe elements and is pushing hard on issues like immigration, Czech sovereignty in EU, and scepticism about climate policies. Forming a government might therefore take longer time.

An alternative solution is a single-party ANO minority government, supported by SPD, the Motorists, and occasionally by KDU-ČSL and the Civic Democratic Party (ODS), as Babiš is likely to want more broad support to avoid the fragmentation and vulnerability that Fico is experiencing in Slovakia.

The challenges of the Spolu-government: Following the 2021 election, Spolu formed a coalition government with Petr Fiala (from ODS) as prime minister to take over after the first Babiš-mandate (2017-21). Since 2021 the political landscape in Czechia saw increased fragmentation and deeper polarization. The main reason for Babiš win in 2025 lies in increased cost of living and disappointment with the Spolu coalition. While in power since 2021, Czechia experienced one of the fastest inflationary developments in Europe. High energy prices considerably impacted the cost of living for citizens, while housing prices grew even faster. Inflation has hit all sectors actually, and wages are struggling to keep pace. A PAQ Research Institute analysis shows that a third of Czechs believe they are worse off than in 2021. So, people below the middle-class level are struggling to some degree, perhaps more than in other countries. The planned increased defense spending, moving toward 3 % of GDP by 2030, will threaten social programs and benefits. Also, Czechia has taken in among the highest proportion of refugees from Ukraine relative to own population, and has been leading the successful Ammunition-for-Ukraine Initiative. The initial nearly euphoric moments of welcoming of Ukrainian refugees have passed, and the attitudes to some degree too. The foreign policy issues related to Ukraine, EU, and NATO are now among key dividing lines in Czech politics.

The successful election campaign: Babiš could easily argue that life became more difficult since he lost power, but he has not suggested substantial reforms or policies to counter that, except for increased pensions and social benefits. Babić’s favoring of more generous social supports and economic populism will have fiscal consequences for the economy. Yet, with his anti-elite rhetoric Babiš is more successful in connecting with regular people than many political competitors. Although he is a billionaire, he still embodies the everyday Czech, with all his everyday failings. This is sympathetic to many Czechs, whose main worry often remains to hinder any “existential threats against drinking their daily tank beer.” Cost of living, and the war in Ukraine are such threats, and current policies of Western partners do not seem to help in bringing an end to the war. There is the idea that if Czechia supports Ukraine too much, it might get Russian revenge, and the 1968 invasion is one such trauma (photo from the Masaryk monument below).

Stronger institutional checks and balances: When comparing Czechia under Babiš with Hungary and Slovakia, Czech civil society and Czech institutions and checks and balances are much stronger and will hinder any autocratic tendencies or fast changes. Even after winning the lower house, Babiš still needs the Senate and this will hinder substantial changes the next years, especially any constitutional changes, which are unlikely. The same goes for the constitutional court, and the secret services. The former president of Czechia, Miloš Zeman, was more likely to open doors for Babiš. The current 2024-elected president, Petr Pavel, can refuse to appoint ministers who support Czechia’s withdrawal from NATO and the EU. The Russian invasion of Ukraine led to increased support for EU in Czechia. However, Czechia remains one of the most EU-sceptical countries. Two thirds are against joining the euro zone, a question which for irrational political reason is absent from the discussion table.

Another difference to Orban and Fico is that Babiš is not revisionist with regard to EU. He is only critical or cautious, seeking to limit climate, migration, and fiscal obligations. Babiš will not go against EU on his own, but may occasionally join EU-critical initiatives fronted by Fico and Orban, as they all share a dislike for liberal democracy. Together with Orban and Austrian FPÖ-leader Herbert Kickl, Babiš last year co-founded the EU-sceptical alliance “Patriots for Europe”. The business interests of Babiš risk damages from anti-EU moves, and Babiš is “a Czech Trump” that thinks in transactional and pragmatic moves more than ideological ones. As a business leader, he will soon have to find a solution to his conflict-of-interest issue for his company Agrofert to be in compliance with Czech and EU law. Moreover, Babiš will be cautious not to alienate Washington.

The influence of Trump in Czechia is clear, and their two mandate periods correspond in time. Thus, the “Strong Czechia”-slogan has obvious inspirations. There is strong cooperation between Czech and MAGA-circles through well-functioning networks. Yet, atheist-inclined Czechia is not overly open for the type of cultural conservatism and religious content like in the US, nor the Christian-nationalist identity politics played by Orban in Hungary. Although Czechia under Babiš will be less critical to Russia, changes will be moderate. Babiš did not make his money in Russia and is not in a dependency position.

Despite media pluralism, the media sector is probably one of more vulnerable spots in Czechia, and it needs a stronger legislative basis. This was also one of the conclusions at the Forum for Journalism and Media based in Vienna at a public session about Czech elections on 24 September (Youtube video). There is massive flow of content from Russian sources being translated and migrated into the Czech information space. Fines from EU are likely, as Czechia did not yet implement the EU Digital Services Act (DSA).

For an assessment of the election from a more technical perspective, contact SEIM Analytics for a consultation.

Post-communist democratization in East Central Europe is a prioritized focus of SEIM Analytics. Read mere about this engagement with Czechia, Slovakia, Poland, and Hungary HERE.

Go to SEIM-Analytics/photo-sale for photos from Czechia

See Seim-analytics/election-expert for further information about lectures, engagements, and professional election assignments in Southeast Europe, Eastern & Central Europe, Caucasus, Central Asia, and South Asia.

The Moravian town of Mikulov. The South Moravia region with the city of Brno and Central Bohemia around Prague saw less convincing ANO wins over Spolu than elsewhere.