Bosnia’s 2022 General Election - Continued Ethnification of Political Competition

7 August 2024, in retrospect

Seconded from Norway to Organization for Security and Cooperation (OSCE) through the NORCAP expert roster, Seim participated in the observation mission of the OSCE/ODIHR to Bosnia and Herzegovina for the general elections on 2 October 2022. Dr. Seim briefed OSCE parliamentarians in the region and organized a dozen teams of short-term OSCE/ODIHR observers for OSCE’s statistical analysis.

Observation area was the Herzegovina-Neretva Canton and the West Herzegovina Canton, including meetings with a wide range of stakeholders, like election officials, political party representatives, media, and civil society organizations. This enabled key inputs to OSCE/ODIHRs Preliminary Statement and the Final Report. More information about the EOM and the joint findings can be found here:

General Election, 2 October 2022 | OSCE

Read earlier OSCE/ODIHR election reports on Bosnia and Herzegovina here

(Photo: The rebuilt Old Bridge of Mostar. It was destroyed in 1994 by the Croat army HVO.)

Disclaimer: The reflections in this blog post of the political analyst and historian Dr. Seim about the continued entrenching of ethnicity as the central organizing principle in Bosnia do not reflect any official OSCE/ODIHR position. Such are exclusively found in the linked-to OSCE reports.

Election results: In the race for the Bosnian Presidency, SDP-coalition candidate Denis Bečirević won over SDA-candidate Bakir Izetbegović with a clear margin. Continued Croat protests after the election system again made it possible for Bosniaks in the Federation of BiH to elect the Croat representative (incumbent Željko Komšić) to the Presidency. The female SNSD candidate, Željka Cvijanović, was elected as Serbian member with a clear margin, yet a tense political contest for the position as President of Republika Srpska between the ruling SNSD head Milorad Dodik and Jelena Trivić of the opposition, with the opposition claiming election fraud. Yet, with a difference of some 29.000 votes, potential irregularities found can likely not influence the outcome. Ruling nationalist parties (SNSD, SDA, HDZ BiH) held their ground, but the growth of opposition parties, e.g., Naša Stranka (NS), Democratic Front (DF), People and Justice (NiP), NES, HDZ 1990, would potentially impacting coalition building.

In the Croat-dominated West Herzegovina Canton and the Croatian-inhabited communities and municipalities in the Herzegovina-Neretva Canton, HDZ BiH remained the hegemonic party. As part of a general electoral engineering, and through various dependencies, HDZ BiH seems also able to influence the votes for smaller Croat parties, dependent upon their support to HDZ BiH (HDZ 1990 was probably artificially supported by HDZ BiH to create the illusion of political pluralism among Herzegovina Croats). The Croatian Republican Party (HRS) leader, Slaven Raguž, declined HDZ BiH cooperation but HRS still achieved mandates. The good HDZ BiH result (and party leader Cvitanović) makes it a key factor for establishing or blocking a FBiH- and BiH-level government.

In the Bosniak communities and municipalities in the Herzegovina-Neretva Canton, the Party of Democratic Action (SDA) and the Social-Democratic Party (SDP) had good results, while some of the Sarajevo-based Bosniak opposition parties received fewer votes than in many other cantons in the Federation.

Campaign visibility was quite good with numerous political rallies. For online campaigning, Facebook was the most used platform. Campaign was also conducted through direct contact with voters by means of city walks, mobile info-desks, and phone calls. Billboards and posters was a key campaign tool. In the Herzegovina-Neretva Canton, the most visible parties were HDZ BiH, HDZ 1990, SDA, SDP, on a minor scale also HRS, DF, and NS.

In the Croat-inhabited West Herzegovina canton, the competition was among Croat parties. Apart from billboards, HDZ had a nearly invisible campaign in Mostar and surrounding municipalities, but many hundred separatist Herzeg-Bosna flags were placed in Mostar before election day.

The rallies observed in Mostar, for instance with Bakir Izetbegović of SDA, SEIM Analytics find to demonstrate that the debate over the recent conflict has become a permanent state of contemporary affairs. This has not changed since Seim followed the 2010 general elections in Bosnia, in Sarajevo City and the Serbian Eastern Sarajevo. On both occasions, war-related political iconography and symbols were everywhere, and political speeches were clearly more focused on problems of the past (the war) than on suggesting solutions for current economic problems.

Contact SEIM Analytics to order/read Seim’s key findings and recommendations on the election administration, political campaigning, civic sector, media sector, voter education, women participation in politics, voting centre adaptation for PWDs, complaints, national observers, voter registry, and the vulnerable position of the Bosnian Serbs.

Approaching 30 years since the end to the tragic conflict, Bosnia appears trapped in this past war, with its resultant post-war traumas and institutional structures, ethno-nationalist election patterns, and divisive memory politics and war commemorations. In the Bosnian “fractured” memory landscape, at least three versions of the past co-exists and clash on a daily basis, defining the political discourse. The last years have seen sharpened political fronts, political instability, and depopulation in Bosnia.

This leads to a research topic/questions of SEIM Academic: The hypothesis that post-war polarizing memory politics and mnemonic conflicts have contributed to Bosnia’s identity cleavages, its current political-institutional dysfunctionality, and has hampered reconciliation. This research project aims to assess these impacts on Bosnia’s state-building efforts. Read more about and contribute to fund SEIM’s research projects here!

From the wider electoral and geopolitical perspective, SEIM Analytics sees the general election in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2022 as another election where hegemonic ethnic-based political parties seem to favour status quo to preserve own political power and related socio-economic advantages. This constellation can even favor their pragmatic cooperation with other hegemonic ethnic political parties across ethnic divides. Continued ethnification of political competition is therefore a part of the political struggle. The continued push (by Sarajevo and foreign powers) for centralization and pressures on political institutions and powers of Republika Srpska is securing the hegemony of ruling nationalist parties there and leads to the narrowing of political debate. The procedures for Croat representation in some administrative bodies, e.g. the Presidency, helped secure HDZ hegemony in these two cantons. It led to the lack of political pluralism and political campaign (for the Croat electorate).

Both factors contribute to political blockades and state dysfunctionality, which however also stems from unitaristic policies of Sarajevo-based parties (civic as well as nationalist Bosniak ones) and it stems from both previous and present OHR policies, having supported Sarajevo’s unitaristic policies. The fact is that this unitaristic Bosnia died in the civil war and with the signing of the 1995 Dayton Accord that divided Bosnia into two equal federal units, Republika Srpska and the Federation BiH. The chronic attacks on Republika Srpska by the OHR and the unitaristic-nationalist politicians in Sarajevo are dangerous, because without Republika Srpska there is also no Bosnia.

New OHR decisions proclaimed on 3 October 2022 might be a step in the right direction regarding the Croat question and representation, but the long-term lack of local ownership of reforms and Bosnia remaining a foreign protectorate remain an underpinning unresolved issue. The postponing of this transition has been undermining the legitimacy of the Bosnian state and contributed to its dysfunctionality.

While awaiting reform, including electoral reform, and preparing for more local ownership to unlock Bosnia’s potential, remaining politically deadlocked, socio-economically underdeveloped, Bosnia is instead losing its younger and educated population through brain drain and emigration, an answer indicating a generational divide developing in society too. The lacking trust in reforms also stems from frequent cases of misguided foreign/OHR interventions after the war (police reforms in the 2000s, removal of democratically elected officials, questionable interpretation of the Dayton constitution, and impositions of legislation and alien symbols of statehood). These actions by foreigners unaccountable to Bosnia have strengthened communitaristic political behaviour, helped limiting political pluralism within each ethno-national group’s own ranks, opened doors for corruption and nepotism, and released domestic politicians of own responsibility, is the assessment of SEIM Analytics.

Bosnia and Herzegovina is the prioritized focus of SEIM Analytics. Seim has followed Bosnia since the early 1990s. This professional engagement in 2022 was an opportunity for an fresh assessment after earlier visits and research in Bosnia in all parts of the country. While other countries in the region is experiencing rapid growth, this is still hampered in Bosnia. OHR-policies towards Republika Srpska and the continued attempts for a unitarist Bosnia are key reasons for this, SEIM Analytics assesses.

Photos above: Another example that the so-called multicultural Bosnia propagated by de-facto nationalist politicians in Sarajevo is fake. Serbian Cyrillic letters are repeatedly being damaged in Bosnia, but Latin letters are rarely tampered with in Republika Srpska. Even the town of Bradina by Konjic — where up to 50 Serbs were killed by Izetbegović’s army in May 1992 or later in the ARBiH concentration camp of Čelebići — after ethnically cleaning the Serbs, also eradicating the Cyrillic letters seems like accepted.

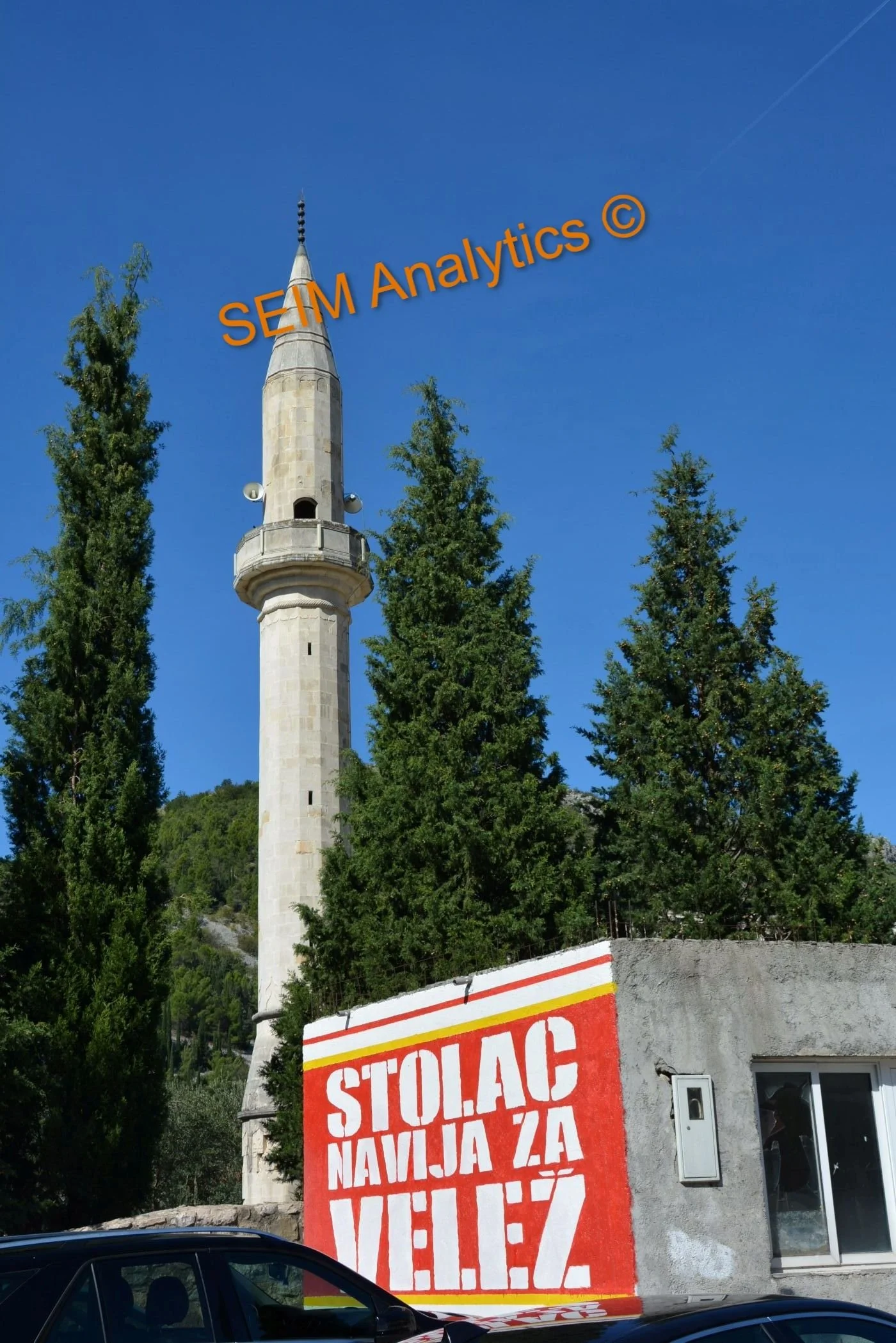

Regional cultural heritage: This EOM assignment was also an opportunity to see historic heritage sites, like Dervish monastery in Blagaj, the Stolac oldtown and the UNESCO-protected Radimlja stećak tombstone necropolis outside Stolac, the famous Medjugorje Catholic pilgrimage site, Počitelj, Mostar oldtown, and the beautiful Neretva valley: See photos below.

Visits were included to the rebuilt Serbian-Orthodox Žitomislić Monastery and the Serbian-Orthodox Cathedral of the Holy Trinity in Mostar that both were destroyed during the ethnic cleansing of Serbs from Mostar and Neretva in 1992 by the Croat HVO and the Bosnian Army. A stop-over in Konjic was included, a site of systematic ethnic cleansing of Serbs in 1992, and Croats in 1993, with Bosnia Muslims as perpetrators. Read Seim’s article “The Muted and Stigmatized: A Case Study of the Ethnic Cleansing of Serbs in Konjic in 1992.” Today, the Serbian population is mostly absent from the Neretva valley after the ethnic cleaning in the war. In the 2013 census, the Serbian share is down to 2.9% in this canton.

This assignment also included trips and meeting in Čapljina, Čitluk, Jablanica, Neum, Prozor-Rama, Ravno, and Stolac. In the West Herzegovina Canton, which is 98% inhabited by Croats, it included visits to Grude, Ljubuški, Posušje, and Široki Brijeg.

See Seim-analytics/bosnia for further information about lectures, engagements, research, newspaper commentary, and professional assignments with Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The rebuilt Serbian-Orthodox Cathedral of the Holy Trinity in Mostar. It was destroyed in 1992 by the Croat HVO as part of the ethnic cleansing of Serbs from the Neretva valley.